Showering with a raincoat on

“Poetry in translation is like taking a shower with a raincoat on.” Now from which movie did I glean that wonderful line??? – Ah, yes: Paterson by Jim Jarmusch. AHA!

But showering with a raincoat on can also be quite a fascinating experience: we feel the drops in an unusual, new and, strangely enough, in a more intense way. As if that secondary skin was at the same time cushioning and amplifying the sensation. Maybe it is because the drops as they hit the fabric will make a noise whereas our skin would absorb them silently?

Here is my latest exercise in raincoat-showering: In a letter to my friend Moshe I quoted one of my favorite poems by Rainer Maria Rilke, “Herbsttag”. This is the German original:

Herr: es ist Zeit. Der Sommer war sehr gross.

Leg deinen Schatten auf die Sonnenuhren,

und auf den Fluren lass die Winde los.

Befiehl den letzten Früchten voll zu sein;

gib ihnen noch zwei südlichere Tage,

dränge sie zur Vollendung hin und jage

die letzte Süsse in den schweren Wein.

Wer jetzt kein Haus hat, baut sich keines mehr.

Wer jetzt allein ist, wird es lange bleiben,

wird wachen, lesen, lange Briefe schreiben

und wird in den Alleen hin und her

unruhig wandern, wenn die Blätter treiben.

Moshe has a smattering of German, but I do not think his command of the language is good enough for him to be able to appreciate the subtleties of rhyme and metre in a foreign language. I tried to find an English translation on the Internet, but none of those that I came across captured Rilke’s masterful play with rhyme and alliterations (e.g. wachen, lange, wandern in the last stanza) even remotely. So eventually I slipped on my poetic raincoat and turned on the shower:

Lord: it is time. This summer was immense.

Now on the sundial cast your shadow,

across the meadows loose let winds.

Command to fullness fruit and vine,

grant them yet two more south’rly days,

press them to ripeness and then chase

last sweetness in the heavy wine.

He who without home will himself not build one now.

He who alone alone will long remain,

will stay awake, will read, long letters pen

and in the alleys wander, to and fro

restlessly, as the leaves drift hence

In memoriam Dino Buzzetti

(1 December 1941 – 23 April 2023)

My first meeting with Dino took place at the 1999 ACH-ALLC conference in Charlottesville, Virginia. The conference turned out a memorable event for a number of reasons. Firstly intellectually, because it was at this conference that the controversy on the OHCO- (“ordered hierarchy of content objects”) model of text erupted, a controversy soon to be labelled the ‘Renear/McGann-debate’ after its two American protagonists. Second anecdotally, because John Unsworth, the local host, convinced almost the entire contingent of computing humanists present to float down the James River on car tubes on a sunny afternoon, Dino and myself included. But most of all I remember this as an equally terrific and terrifying experience because of what happened at the very end of the conference, in the final three-speaker slot shared by Dino, Claire Warwick and myself.

Due to a last-minute change in order Dino was appointed as the second-last speaker, and he delivered a paper titled “Text Representation and Textual Models”. It was an excellent paper (more on that in a second) and a hard act to follow, and so I went to the front of the room with some trepidation to deliver my own contribution — as chance had it now the very final paper of the entire conference. I had prepared everything as best I could; my notebook with the PowerPoint presentation was set up, my manuscript lay on the lectern, ready to be read. Or so I thought – for when I got there the manuscript was: gone. A couple of very frantic moments later it transpired that Dino had accidentally bagged it at the end of his talk, together with his own manuscript… From then on whenever Dino and I met over the course of the following years I reminded him of the moment he stole my manuscript. This frantic moment was the beginning of our friendship, a friendship that lasted for almost quarter of a century.

Let me fast forward to our very last meeting. This happened in 2020, in the historic Aby Warburg-house at Hamburg University where my colleagues bid me farewell on my retirement with a wonderful symposium. Dino was one of four old-school, ‘bedrock’ computing humanists who honoured me with their presence — colleagues who, like myself, were already active in the field in the 1980s and 1990s, when it was still known as Humanities Computing (the other three present that day were Manfred Thaller, Willard McCarty and John Bradley). I was deeply moved, and I still remember the private exchange that Dino and I had after the official part had been concluded. I remember Dino’s voice, his smile, how he used to raise his eyebrows, everything.

And of course, I do remember Dino for the outstanding philosopher that he was. Like Father Busa and Tito Orlandi, Dino came from an intellectual and cultural background which over the centuries had learned to elegantly and productively bridge a fundamental philosophical divide, namely that between deep theological speculation on the one hand, and Renaissance-inspired methodological curiosity about how one might explore the human condition in novel, undogmatic ways. The paper which Dino presented in 1999 at the ACH-ALLC conference is well worth re-reading in this regard. It was expanded on in his 2002 article in New Literary History titled “Digital Representation and the Text Model” – a seminal publication which I personally consider to be the most thought-provoking and philosophically stringent contribution to the OHCO- and MarkUp-debate to date. Dino came back to the topic time and again, one instance being a panel discussion with Manfred Thaller at the DH 2012 in Hamburg that had the audience mesmerized. I will never forget the expression of awe on a young colleague’s face who termed the event “the Manfred and Dino Show”.

Dear Dino, I thank you for your friendship and the stimulating exchanges we had, for the elegance and warmth which you brought to both. Today as in 1999 at our very first meeting it turns out that I am the one who has the last word – for now. Because I cannot help thinking of that classic scene in Wim Wenders’ “Wings of Desire” where Peter Falk, munching a greasy burger roll at a Berlin Hot Dog stand, suddenly startles, smiles and then addresses Gabriel, the invisible angle: “I cannot see you. But I know you’re there. Compagnero.”

Chris

Gernhardtscher Osterspaziergang 2017

Ballade von der Lichtmalerei

Leg etwas in das Licht und schau,

was das Licht mit dem Etwas macht,

dann hast du den Tag über gut zu tun

und manchmal auch die Nacht:

Sobald du den Wandel nicht nur beschaust,

sondern trachtest, ihn festzuhalten,

reihst du dich ein in den Fackelzug

von Schatten und Lichtgestalten.

Die Fackel, sie geht von Hand zu Hand,

von van Eyck zu de Hooch und Vermeer.

Sie leuchtete Kersting und Eckersberg heim

und wurde auch Hopper zu schwer.

Denn die Fackel hält jeder nur kurze Zeit,

dann flackert sein Lebenslicht.

Doch senkt sich um ihn auch Dunkelheit,

die Fackel erlischt so leicht nicht.

Sie leuchtet, solange jemand was nimmt,

es ins Licht legt und es besieht,

und solange ein Mensch zu fixieren sucht,

was im Licht mit den Dingen geschieht.

Robert Gernhardt, in: Robert Gernhardt, Peter Rühmkorf: “In gemeinsamer Sache.” Reinbek bei Hamburg (Rowohlt), 2002, S.27

Rühmkorf(f)scher Osterspaziergang 2017

Vom Zielen und vom Zittern

Das Leiden denkt, es würde ewig währen.

Im Gegensatz zu unserer lieben Lust –

Die ist sich ihrer Endlichkeit bewußt

und andererseits geneigt,

sich mit Bedenken zu beschweren.

So scheint die Welt kein Nervenruhekissen.

Z.B. wo du in Verfolgung eines Zieles

– sagen wir, einer bang begehrten Braut –

bereits im Anflug ahnst, sie würde dir entrissen:

Sie wird! Zu Recht. Und so entgeht dir vieles,

weil aus verzagten Friedhofsaugen angeschaut,

ist die Partie meist schon im vorhinein verschmissen.

Selbst das Gedicht, das sich zu skrupelvoll bedenkt,

führt auf die Stufe zu,

wo sich dem Vers der Fuß verrenkt.

Peter Rühmkorf

in: “Paradiesvogelschiß.” Reinbek bei Hamburg (Rowohlt) 2008, S.110

Badewanne der Träume. Deutsches Schauspielhaus Hamburg, 5.12.2015

Gestern Abend im Hamburger Schauspielhaus die Premiere von “Schiff der Träume. Ein europäisches Requiem nach Federico Fellini” in der Regie der Intendantin Karin Beier gesehen. Was in den ersten 60 Minuten konzentriert als Schauspielkunst der kritischen Selbstreflexion des Künstlerischen begann, soff in einer über mehr als zwei Stunden ausgewalzten Peripetie in einen postpubertären Multikultiklamauk ab, der sich für keine Platitüde und keinen Griff in die inszenatorische Klamottenkiste zu schade war.

Nachdem die erste Partie noch relativ nah am Fellini-Original das egomane Kreisen der Kunst um die eigenen Befindlichkeiten analytisch auffächert und den Schauspielern immerhin die Möglichkeit eröffnet, das zum Zustand geronnene Sein mit den ihnen eigenen Mitteln von Sprache, Bewegung, Gestik und Mimik auf dieser weiten Bühne, vor einem großartigen Bühnenbild mit klugen Projektionen im Hintergrund, im Diskurs mit einem subtilen musikalischen Dialogpartner und von der Lichtregie im tieferen Sinne ‘beleuchtet’ im Ensemble auszuloten und ihm so Nuancen abzugewinnen, die dem Zuschauer ein neues Auffassen und Verstehen abverlangen, zieht die Dramaturgie diesem “Schiff der Träume” mit dem Auftritt der fünf Weisen aus dem Morgenland – aka: afrikanischen Flüchtlinge (oder sind es eher Migranten? who cares; Hauptsache, sie sind schwarz) – jäh den Stöpsel heraus.

Und es zeigt sich: das Schiff ist eine Badewanne, in der eine Truppe hip-hoppender Hanswurste, die als mediterrane boat people verkleidet wurden, clash-of-cultures Phrasen zu Betroffenheitsschaum schlagen. Der wird dann mit viel Körperakrobatik und einem gegen Null gehenden Schauspieltalent drei- oder viersprachig ins pflichtschuldigst betroffene Publikum hinein getrötet. Sozusagen als Einladung, jetzt gefälligst selber in die Wanne zu steigen und sich ein wenig darin zu suhlen. Irgendwann (man fragt sich: warum eigentlich? Ach so, ja; wir müssen die ganze Chose, die man uns eigentlich schon hinlänglich qua Publikumsadresse und obligatorisch-interaktiver Einlage im Diesseits der vierten Wand erklärt hat, auch noch auf der Bühne nachgestellt bekommen. Wir sind doch im Theater – Mensch, fast hätte ich’s vergessen!) tritt dann auch wieder die eigentliche Schauspielkompagnie auf.

Und sie müht sich redlich, mit den uns Europäer endlich, endlich mit der profunden Erkenntnis unserer Bigotterie konfrontierenden und zur Veranschaulichung gelegentlich auch einmal minutenlang schön-schaurig im Trockendock “Schauspielhaus” ertrinkenden, dabei aber insgesamt recht fröhlichen edlen Wilden (sind übrigens alle drahtig, männlich, unter Dreißig. Schade – man hätte sich doch auch noch ein gerüttelt Maß Genderproblematik gewünscht!) ins Gespräch zu kommen. Ein bißchen Karikatur des kulturellen Fremdelns, ein bißchen Begegnung zwischen europäisch-hochkulturellem Menuett und afrikanischem Bass and Drums; am Ende auch gar ein wenig kulturverbindendes Line Dancing. Aber das reißt jetzt selbst ein Charlie Hübner, eine Perle von Rampensau, wie er an zwei, drei Stellen des Stückes zeigt, nicht mehr wirklich.

“Schiff der Träume. Ein europäisches Requiem nach Federico Fellini” in der Regie der Intendantin Karin Beier ist eine plakative Peinlichkeit verklemmter political correctness. Kein Fettnapf des abgestandendsten Gedankenschmalzes, in den hier nicht gesprungen wurde: ästhetizistischer Ennui, Eurozentrismuskritik, Gutmenschenbashing, Schlechtmenschenlob, Schlechtmenschenbashing, Gutmenschenlob. Sehr, sehr viel Vordergrund und einfache Antworten, die gleich wieder zurückgenommen werden. Immerhin; am Ende ein gediegen konfuser, mit Verve vorgetragener Schlussmonolog der Diva vor einem bühnentechnisch schön gemachten Schiffsuntergang des “European Cultural Cruises”-Liners. Das Stück als ganzes jedoch trivialisiert ästhetische wie moralisch-ethische Orientierungslosigkeit in einer konfusen Montage von bereits Gesagtem, Gedachtem und Gesehenem – was nicht ganz das Gleiche ist wie ein “poetisch-dramatischer Aufruf zur Kursänderung”, als den die Ankündigung im Spielplan den Filmklassiker von 1983 immerhin korrekt versteht. Über den schrieb Morando Morandini am 7.10.1983 in “Il Giorno”:

“Fellinianisch ohne Fellinismen (…) alles steht unter dem Zeichen der Trauer, ist jedoch heiter und sanft detachiert; reich an vielen Schönheiten, jedoch ohne inszenierte Übertreibungen; manchmal alarmierend, manchmal beängstigend, aber auch unterhaltsam, lustig, durchdrungen von einer ruhigen und vorsichtigen Liebe zum Leben. (…) Fellini mildert seine Vorliebe für die Karikatur, die scherzhafte Verhöhnung, die Monstrosität: in Bezug auf die Personen ist Zuneigung zu spüren, mit einem kritischen Detachement und vor allem mit Respekt.”

Das wäre in etwa eine Kritik ex negativo der gestrigen Premiere. In Fellinis Film gibt’s übrigens am Ende ein Nashorn im Rettungsboot; zu dieser Reverenz an Ionesco hat’s im Schauspielhaus nicht mehr gereicht. Honi soit qui mal y pense, leben doch die Nashörner in Afrika.

Weaponizing the Digital Humanities

Today is the last day of the DH 2014 conference at Lausanne – a marvellous event both intellectually and socially! For those who don’t know the acronym: the annual “Digital Humanities” conference is the largest and most important conference for the international DH community and this year attracted a record-breaking 700+ delegates from all over the world – so the bar has been raised once again.

Unfortunately, the DH no longer attracts scholars only. Today I sat in a session that was also attended by a delegate wearing an unconspicously-conspicous affiliation badge identifying him as belonging to “US Government”. That’s a designation commonly known to be long-hand for NSA and the likes. Just ask such a person for a business card or their contact details (though I’m sure that by next year they’ll have resolved that issue as well).

Did this surprise me? Not really. I have myself been contacted twice (i.e., through US academic colleagues) with an offer to consider participation in projects which are funded by the NSA and similar intelligence agencies. And let us not be naive: the more attention DH researchers invest in Big Data approaches and anything that might help with the analysis of human behaviour, communication and networking patterns, semantic analysis, topic modeling and related approaches, the more our field becomes interesting to those who can apply our research in order to further their own goals.

This is the nature and dilemma of all open research: we are an intellectual community that believes in sharing, and so unless we decide to become exclusive, there’s no stopping someone from exploiting our work for other purposes. Moreover, all of us who are on an institutional pay-roll are effectively funded by the same body that also channels funds (and lots of it) to military and defense. But it is one thing to entertain this thought in an abstract manner and quite another to realize how bluntly these agencies have begun to operate within our own community. In this particular instance we witnessed first-hand how the “US Government” labelled delegate immediately engaged with one of the younger presenters. My guess is that one of my colleagues has today lost his research assistant to a better paid job.

It is high time for us to realize that we are now facing the same moral and ethical dilemma which physicists encountered some 70 years ago when nuclear research lost its innocence. What is happening right now, right here is this: our scholarly motivation is being openly instrumentalized for a purpose that is at its very core anti-humanistic. One might of course argue that we need to differentiate between the philosophical and political principles of enlightenment on the one hand, and the necessities of protecting society as well as individuals against acts of crime and terrorism. But even if we decide to adopt such a pragmatist view it is hard to ignore that the apparatus has spun out of control and operates in a fashion that is completely intransparent. What is being presented as a necessary impingement on constitutional rights for the sake of protecting those rights is increasingly drifting towards a neo-McCarthyist attempt at social engineering.

To date all evidence points to the fact that

- the benefits of massive and indiscrimenate surveillance of citizens by intelligence agencies have been marginal;

- the negatives of this activity are being consistently downplayed, if not fully ignored. Perhaps the most alarming of these negatives is the increasingly cynical attitude adopted by us, the victims of these activities, who with absurd pride claim to have been ‘in the know’ anyhow, and who have resorted to downplaying our ethical and philosophical capitualition as a sign of being ‘realists’;

- the political mechanisms to control security agencies and the military have failed, or are at the brink of failing.

In other words: massive surveillance has failed to demonstrate its legitimacy on quantitative grounds, it ignores the qualitative damage to society, and it has begun to circumvent constitutional mechanisms. The security establishment has managed to construe a neat double-bind in which democratically elected governments find themselves entangled – shut-up and be safe.

DH now runs the risk of playing into the hands of those who execute this policy as our community’s research interests have begun to take on a more sociological orientation. In that perspective a DH study into the complete works of Chaucer is of little relevance both in terms of contents and in terms of methodology. But a DH study into the behavioral and sense-making patterns of the community of Chaucer readers is not.

So far we have turned a blind eye on this aspect of our work. The only way in which our community can counter this development is to do the exact opposite: bring the issue out into the open and start a debate. ADHO – the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations – has recently adopted a “Code of Conduct” for its conferences which states among other that there

“… is no place at ADHO meetings for harassment or intimidation based on race, religion, ethnicity, language, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, physical or cognitive ability, age, appearance, or other group status. Unsolicited physical contact, unwelcome sexual attention, and bullying behavior are likewise unacceptable.”

I propose that we formulate a similar Code with regard to an activity that is equally unacceptable: the infiltration and weaponizing of the Digital Humanities by government agencies.

re-mapping the body

“re-mapping the body” was a dance performance which I saw on 9 July 2014 at the DH 2014 in Lausanne. The show was a performance by Company Linga, with choreography by Kataryna Gdaniec and Marco Cantalupo. I found this a very moving expression of how the human body interacts not only with the topographical space around it, but also with the soundspace in which our doings are embedded. This Facebook clip shows a solo piece danced by Ai Koyama.

Introductory comments in the clip are taken from the announcement on the DH 2014 conference website – for the full credentials (including photography) please visit http://dh2014.org/affiliated-events/re-mapping-the-body/

To watch the clip in high resolution, please click the image below. Please note: the mp4 file is 100 MB, so it will take some time to download.

For more information see www.linga.ch / +41 21 721 36 03 / info@linga.ch

Many thanks to the local DH 2014 organizers Claire Clivaz and Frederic Kaplan for this wonderful addition to an enriching academic programme!

Flann O’Brien, “The Third Policeman”

If ever you grow tired of pondering life’s miracles, read Flann O’Brien’s “The Third Policeman” (written 1939-1940; first published post-humously in 1966). It’ll re-instill in you an inexhaustable trust in the absurdity of being!

“Never before had I believed or suspected that I had a soul but just then I knew I had. I knew also that my soul was friendly, was my senior in years and was solely concerned for my own welfare. For convenience I called him Joe. I felt a little reassured to know that I was not altogether alone. Joe was helping me.”

Flann O’Brien, The Third Policeman

Flann O’Brien was one of the pseudonyms of Brian O’Nolan (Irish: Brian Ó Nualláin; 5 October 1911 – 1 April 1966)

For a lot of exquisite & hilarious quotes from the novel, see here.

Edwin on the dreamline

27 June 2014. At the end of a long day – which isn’t quite accurate as it’s 1:15 am and thus already the next day – and as I’m about to drop into my hotel bed in Berlin after a REALLY long day and then a couple of beers and cocktails with Thomas in the spaced out, Lost-in-Translation-like hotel bar at the Park Inn (what were we talking about? John Willams’s ‘Stoner’; W.G. Seebald; the fact that most contemporary German literature doesn’t speak to us; ah yes: Heidegger and Gadamer and the strange obsession with professing allegiance to a ‘teacher’ that is characteristic for German academics. I will never get this: supposedly grown-up individuals regressing into primary school lingo and idolizing their intellectual heroes, most of whom were clearly as bright and original as they were troubled, pretty much like all of us are. Anyway, that’ll be another blog… but you’ll see the connection just now) I check my mobile and there’s a message from Angela. Our friend Edwin is dying. He’s been in the ICU at George Provincial Hospital in South Africa for three weeks, in an artificial coma, and now his organs are packing up and someone’s about to act courageously and compassionately and switch off the respirator.

Blank. It takes a couple of seconds to sink in. Last time I saw Edwin must have been about 9 months ago; he was about to move to De Rust after finally loosing the battle over the Karoo family farm Omdraisvlei. It is so remote and in the middle of nowhere that you can actually find it on some old terrestrial globes. And it is so remote that Google doesn’t know it and I should actually misspell its name here (have I?) to protect a dream from the cognitive fascism of machine learning and the idiocy of recommender algorithms. This is how it works:

Imagine 25.000 hectars of semi desert, with Bushman paintings, the remains of an airstrip and a school house and a train station and black rocks and table mountains and endless skies and lone sheep and a patch of green grass irigated by wind motors that pump up ice cold water from 80 m below and glistening sheets of corrugated iron on the walls of the barn where the shearers sweat in 45 degree heat and heaps of wool get sorted into huge boxes and Edwin stands outside the farm kitchen the next morning with a mug of coffee in hand and it’s 6 am and he’s smiling and in the evening he will crank the handle of the old lister diesel generator and the machine will hammer through the icy Karoo night and the lights will go on and then eventually they will go off again and we’ll sit around the fire and Edwin will be full of stories, so full of stories, and you listen to him and you realize, this guy is crazy, seriously crazy, crazy in the most heartwarming and inspiring way, and yes, not everything about this is nice and there is quite a bit of collateral damage to come; he and Sue will break up, but for now it is still 1988 and we have just met him and Sue for the very first time on our very first trip from Johannesburg to Cape Town, Johnny told us about Edwin and that we’d be welcome there, and we just popped in without prior notice and even if Johnny did indeed tell Edwin about us coming Edwin had clearly forgotten or didn’t find it important for visitors to be announced – remember, we’re talking 1987: no cell phones, no internet – and in 1994, on our last journey to Cape Town before leaving SA for a couple of years, we’re at the farm again and I see: the huge wind pump next to the garden, a massive thing over 25 meters high, imported from Australia by Edwin’s dad or granddad and apparently once the highest in South Africa, is shattered to bits, the rotor blades flapping aimlessly in the breeze with a creaking, metallic noise, and it was then that I realized: from here on it’s down hill.

But I only realized that I had realized that then quite some years later. All of us kept on living, fighting, marching on with the determination of ants. And who’s to judge; at least we tried and we didn’t whimper either (here’s the connection with German contemporary literature and ‘Stoner’, this touching hymne to the stoicism of deed and language). Edwin in particular didn’t whimper. 15 years ago he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Last time I saw him he was, simply put, frail, no doubt about it. But his mind was not just on fire – it was by then radio-nuclear and he still didn’t know any half-measure in anything. If a candle had three ends instead of two, Edwin would have lit them all. Which, as I said before, was not always nice, let alone fair to those who tried to be close to him. But he had a soul, and best of all: he didn’t need followers. I remember that in his first autobiographical account which he self-published he describes how he enters the dining hall in a Parkinson’s clinic for the very first time and there’s this strange rustling, like a gust of hot air tearing at the corrugated iron sheets of the barn on his farm, and he realizes: it’s the cutlery of the patients clanking on the enamel plates, and so he decides to join the symphony of the shaking limbs.

I sat down (we’re back in Berlin) and wrote an eMail to Angela:

I fall asleep with this image of Edwin, standing at the head of one of the countless dreamlines he explored during his life time.Three hours later I wake up in my 22nd floor East facing hotel room. The sun rises over Berlin, a glowing red eye looks straight at me, inquisitive. And I understand: Edwin’s on the trail of trails

It was a blessing to have met him and to have enjoyed the privilege of a glimpse into his world, contorted and idiosyncratic as it might have been and is destined to remain forever after.

Fare well, Edwin, compagnero: we’re bound to meet on the other side. May your journey be peaceful and fulfilling.

I’ve seen fire and I’ve seen rain

I’ve seen sunny days that I thought would never end

I’ve seen lonely times when I could not find a friend

But I always thought that I’d see you baby, one more time again…

James Taylor, ‘Fire and Rain’. A line I once wrote under a photograph taken of the broken windmill at Edwin’s farm in 1994.

PS: Who needs ‘teachers’ as long as we have companions?

BottomBottom

The bottom holds

youth, lust, bewilderment, and trust

the residue of all that was

the foreshadow of all that must

be lived.

In ten years time I will recall

the moment that is now and how

the joy it held has all been sieved.

Good luck, my friend, each one of us

a dweller of his future hell

spellbound to this, the well

of presence and its shining past.

The duskless dawn approaches fast

a flake sinks to the bottom

of my glass.

Zu Uwe Timms “Vogelweide”

Und auf die Frage, warum sie das alles so selbstverständlich entgegennahm, aber sich nichts von ihm hatte schenken lassen, sagte sie mit dem weichen polnischen Akzent: Weil du von mir dir kein Kind hast schenken lassen wollen.

Wie kompliziert dieser Satz war und das, was er bedeutete.

Uwe Timm, Vogelweide. Köln 2013, S.279

Treffender als jede wortreiche Herleitung eines Geschmacksurteils und als jede Umschreibung von Inhalt, Komposition und Thematik weist dieser kurze Passus, in dem sich die Stimme des sich erinnernden Protagonisten Eschenbach und die seines Erzählers berühren, auf das ästhetische Anliegen der Erzählkunst von Uwe Timm. In der Sprache seiner Texte begegnen und durchdringen sich die Dinge mit ihrer lautlichen wie gedanklichen Spiegelung. Die Sorgfalt, mit der ein Satz wie dieser von Timm gestaltet wird, verlangt zunächst ein genaues Beobachten dessen, was außerhalb seiner liegt, und dann ein Erkunden der Worte in jenen Dimensionen, die ihnen noch vor der Einpassung in die Syntax ein Eigengewicht verleihen. Dieses Eigengewicht schlägt sich in einer eigentümlich archaischen Dynamik nieder – einer Dynamik, die man zwar analytisch als die von Etymologie, Semantik und Prosodie kennzeichnen könnte. Aber das Analytische und seine trennscharfen Konzepte treffen es nicht; dem Phänomen, um das es diesen Texten geht, wird eine weichere Umschreibung – etwa als Wechselspiel von Laut und Bedeutung – gerade deshalb besser gerecht, weil sie eben keine unbeteiligte Objektivität suggeriert, sondern unser je eigenes Angerührtsein von den Worten mitdenken läßt.

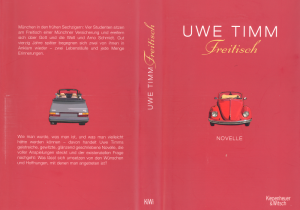

Dieses Hinhören auf die Worte, dieses sich Einlassen auf ihren Eigensinn und ihre Geschichte und dieses Innehalten, bevor man sie in einen Satz und die Sätze in einen Text spannt, sind Uwe Timm schon immer ein Anliegen gewesen; das Thema wird in seinen poetologischen Texten wie in seinen Erzählungen und Romanen immer wieder aufgegriffen. Und doch kenne ich keinen schöneren, stimmigeren Satz von ihm als dieses „Weil du von mir dir kein Kind hast schenken lassen wollen“, in dem der Fluß der Alliterationen in einem harten Kontrast steht zu der sperrigen, Konzentration erzwingenden Wortstellung. Melodie und Syntax spiegeln hier aufs Exakteste den Widerstreit, der in und zwischen den beiden Figuren Selma und Eschenbach erst in einem Moment der Reflexion auf Vergangenes zu Bewußtsein kommt. Die Sprache vollzieht hier nochmals nach, was an der Erfahrung zwar vorbeigerauscht war, aber in den Herzen der beiden haften geblieben ist. Selma, „die Silberschmiedin, mit der er seit zwei Jahren zusammen war – denn zusammenleben konnte man, da sie getrennt wohnten, nicht sagen“ und einem Freund Eschenbachs mit ihrer Weichheit „einem doch recht rückständigen, wenn auch sehr angenehmen Frauenbild“ zu entsprechen scheint, ist alles andere als passiv: sie gibt sich nicht hin, sie entscheidet sich zur Hingabe. Aber dieses Geschenk verwirrt den Helden und verängstigt ihn; er flüchtet sich in das Begehren nach Anna. Und so nimmt eine Katastrophe ihren Lauf zu einem guten Ende. Begehren, Liebe, Verlust sind die drei Leuchtfeuer, die ihren Streifen immer wieder über den weiten Nordseehimmel streichen lassen, den unser Held als Vogelwart nach seinem geschäftlichen wie emotionalen Bankerott in der aufgehypten Metropole Berlin jetzt von der Veranda seines Wohncontainers auf einer einsamen Elbinsel aus mustert. Es sind drei große Themen, und der Roman wird ihnen gerecht, auch wenn manches an Verpackung und Drumherum verzichtbar gewesen wäre. Das beginnt bei der etwas knirschenden Wahlverwandschaften-Mechanik der Figurenkonstellation; es setzt sich fort bei der bemüht herbeizitierten und ins Figurentableau montierten „Norne“ – einer Meinungsforscherin, in deren Auftrag Eschenbach nach seinem unternehmerischen Scheitern als Chef einer Softwareentwicklungsfirma, die sich auf Prozessoptimierung spezialisiert hat, per Marktanalyse die statistische Logik des Paarungsglückes erkunden soll. Warum um Himmels Willen Uwe Timm diese Attacke auf Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann reitet, habe ich nicht begriffen. Abgesehen von der Peinlichkeit dieser verklemmten Schlüsselromanassonanz ist auch die Figur als solche nicht stimmig. Intertextuell verweist sie auf die Unberührbare aus Timms „Halbschatten“, erstens weil auch auf sie der begehrliche Blick Joseph Goebbels fällt, und zweitens weil sie ihr in ihrer emotionalen Kühle gleicht. Aber sie gehört schlicht nicht in die gleiche Welt wie Eschenbach, und man nimmt ihr auch nicht das philosophische Interesse an einer Erkundung der Bedingungen menschlichen Glückes ab. Gedanklich ist es zwar richtig und wichtig, wenn der Roman-Diskurs über Begehren und Liebe sich der Frage widmet, inwieweit es nicht gerade die Kontingenz des Partnerglücks, des Glücks-Falles in Liebe und Vertrautheit ist, die wir uns bewahren müssen in einer Welt, die mehr und mehr auf den planbaren short term benefit von algorithmengesteuerten Recommender-Systemen setzt. Daß das Vertrauen auf die Statistik uns die beseelende Erfahrung des Kairos, des glücklichen Momentes raubt, weil sie uns die lustvolle Preisgabe an existentielle Risiken austreibt ist ein ebenso wichtiger Gedanke des Buches wie der, daß das Glück kein bei amazon.com oder parship.de orderbares Produkt ist, sondern ein von uns selbst zu gestaltender Prozeß. Es sind kluge und lebensweise Reflexionen, zu denen Timm seinem Helden da verhilft: „Das Glück des Augenblicks, sage ich, das Zugreifen, der Kairos, verstehst du, das ist Teil der Paargeschichte, der Fehler wie des Geglückten, das ist die Energie, die in kalten Zeiten wärmt…“ (273). Aber er handelt sich damit zugleich das ästhetische Dilemma ein, sich passagenweise hart an der Grenze zum Ideenroman zu bewegen. Einer Figur wie dem Ich-Erzähler und Begräbnisredner in Timms großem Roman „Rot“ hat man so einen Intellektualismus ohne weiteres abgenommen; in anderen Texten wie dem leichtfüßigeren „Freitisch“ hat Timm solchen Ernst doppelt zu brechen gewußt, und zwar mit Komik, mehr noch aber Dank einer gedoppelten Erzählperspektive, die einen autodiegetischen Ich-Erzähler zusammen mit einer Erzählfigur auftreten läßt, die ihrerseits erkennbar der ‚Vorwurf‘ für die Figur Eschenbach war. Auf der Szene der “Vogelweide” hält man jedoch vergebens nach so einem ästhetischen Gegengewicht Ausschau; man ist mit dem Helden Eschenbach allein und gefangen in Reflexionen, die mal die seinen sind und mal solche, denen er die Stimme leiht. Dafür gibt es immerhin den einen oder anderen kleinen Scherz am Rande: in „Freitisch“ fährt der zum Mülldeponieentwickler avancierte Alt-Achtundsechziger aus Berlin ein graues Saab-Cabrio; der farbenblinde Designer des Buchcovers hatte für uns daraus aber ein rotes gemacht (NB: siehe das Postscriptum unten!) Das Lifestyle-Gefährt aus Schweden ist zwischenzeitlich offenbar direkt in Eschenbachs Berliner Garage gerollt – bis die Gerichtsvollzieherin kommt. Solche augenzwinkernden Querverweise sind ebenso typisch für Timm wie es seine Gabe ist, stimmige Nebengeschichten und Nebenfiguren einzuflechten: ein Hafis und Goethe lesender persischer Nachbar im Berliner Plattenbau-Mileu; ein Obelixzauberer, der uns die Leichtigkeit des Seins aus der Nase zieht; eine Bankertochter im Kostüm, die zusammen mit ihrem gegeelten und prachtgebissigen Partner mal eben aus dem „Rot“-Universum zu uns überwechselt. Aber das sind letztlich alles nur narrative Schmankerl für die Timm-Gemeinde. Wer sich (noch) nicht dazurechnet, wird andere Fragen stellen und Beobachtungen machen. So wirft Sandra Kegel in ihrer Rezension dem Buch vor, es versinke im Anspielungssumpf:

Wie gern hätte man von diesem Autor etwas Überraschendes oder gar Neues über das Begehren erfahren. Stattdessen wirft er einen überreflektierten Blick auf unsere Wirklichkeit, der zu stereotypen Bildern führt. Der indianische Liebhaber, der Überlebenstraining in der Schorfheide anbietet, bleibt so behauptet wie der Stararchitekt, der Wohnsiedlungen in China baut, oder Annas wundersame Karriere als Erfolgsgaleristin in Amerika. Gern hätte man auf Keats und Goethe, Luther und Luhmann verzichtet, wenn man dafür mehr Uwe Timm im Original bekommen hätte.

Wenngleich ich für meinen Teil durchaus mehr und neues über das Begehren erfahren habe – die Einwände zur gewollten Assemblage des Personals sind ebenso Ernst zu nehmen wie die zur Zitatenmontage; es wäre gewiß auch ohne den Nachweis der Belesenheit gegangen. Umsomehr jedoch gereicht für mich Timms „Vogelweide“ zum Verdienst, daß in dieser Welt die tiefgründigsten Verweise nur angedeutet und vom Text behutsam knapp unterhalb der Wahrnehmungsschwelle gehalten werden. Daß der Held Eschenbach nichts mit dem Dichter des Parzival zu tun hat, wird uns zwar explizit gesagt; wieviel Gustav von Aschenbach jedoch in dieser Nordseevariante Veneziens wiederauflebt, darüber darf der Leser selber nachdenken – und auch darüber, ob es überhaupt sinnvoll ist, so einer Spur aus der fiktionalen Welt in die der Texte zu folgen. Denn die wichtigeren und wirkungsmächtigeren Spuren sind bereits in der Sprache gelegt, vor allen Dingen in der eigentümlichen, das mittelhochdeutsche „guot“ anklingen lassenden Redeweise Selmas:

Ich hoffte, du wirst mir wieder gut sein. Und jetzt? Später war es dieses Bild, das ihm immer wieder, wie auch jetzt, vor Augen kam und ihm für einen Moment den Atem nahm: Ihr stilles Weinen, in dem kein Vorwurf, nur Trauer war, und diese altertümliche Wendung: Du wirst mir wieder gut sein. Und wenig später war sie Ewald gut.

Das ist die Hoffnung, die dieses kluge Buch – trotz seiner kompositorischen, figürlichen und motivischen Ausreißer und seiner ‚Überreflektiertheit‘ (Kegel), die mancher ihm vorhalten mag – zu vermitteln weiß und gerade im Unausgesprochenen bekräftigt: daß wir einander gut sein mögen und vielleicht selbst angesichts des Begehrens gar treu, soweit unsere Kräfte eben reichen. Es ist eine Hoffnung, der zu Beginn der deutschen Literaturgeschichte einer Ausdruck verliehen hat, der diesem Roman zwar seinen Namen leiht, aber allenfalls noch in Gestalt des Falken aus dem späteren Lied des Kürenbergers um 1300 körperlich wie thematisch in ihm präsent sein mag. Dieser Namensgeber dichtete vor 800 Jahren:

Wol mich der stunde, daz ich si erkande, diu mir den lîp und den muot hât betwungen, Sît deich die sinne sô gar an si wande, der si mich hât mit ir güete verdrungen. Daz ich gescheiden von ir niht enkan, daz hât ir schœne und ir güete gemachet, und ir rôter munt, der sô lieplîchen lachet.

(Gelobt die Stunde, da ich sie erkannte, Die Leib und Seele mächtig mir bezwungen, Wo ich gebannt zu ihr die Sinne wandte, Die sie durch ihre Tugend mir entrungen! Daß ich ihr folgen muß, nicht anders kann, Das wirkte ihre Schönheit, ihre Güte Und ihres Lachemundes rote Blüte.

Nachgedichtet von Richard Zoozmann (1863-1934). In: Walther von der Vogelweide aus dem Mittelhochdeutschen übertragen eingeleitet und mit Anmerkungen versehen von Richard Zoozmann. Herausgeber: Jeannot Emil Freiherr von Grotthuss Druck und Verlag von Greiner und Pfeiffer Stuttgart 1907 (S. 18))

JCM, 20.11.2013

Postscriptum (28.10.2014): Von wegen “farbenblinder Designer des Buchcovers” – ‘markenblinder Betrachter’ müsste es heißen! Und ich leiste deshalb hier Abbitte bei Rudolf Linn, dem Designer des Umschlags, denn: der Saab ist auf der Cover-Rückseite sehr wohl im dezenten Grau und in Rückansicht abgebildet; rot prangt auf der Vorderseite vielmehr ein Käfer-Cabriolet, das dorthin direkt aus dem Inneren von “Freitisch” gerollt sein muß, denn dort macht sich der Held der Erzählung in einem solchen, geliehenen Wagen auf den Weg zu Arno Schmid: “Die Bekannte hatte ihn gewarnt, der Wagen, ein Cabrio, sei alt und das VW bedeute: Fehlerhafter Wagen. Beim Losfahren habe er noch überlegt, ob sich in dieser Redensart der Bildungsnotstand zeige, der damals schon beklagt wurde (…)”, S.40.

reverse thinking: from NSA to BND

How about a little thought experiment:

Gerhard Bauden, an encryption specialist employed by, say, SAP who has been seconded to the BND (Bundesnachrichtendienst, Germany’s NSA) flees to Iceland. Holed up at the Reijkjavik Hilton he leaks classified documents to the Swiss Newspaper “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” which, if proven to be genuine, uncover a huge digital spying operation conducted by the German secret service targeting, among other, not only the entire US population, plus that of Canada, Australia, and rogue nations such as Ireland and the UK, but also US embassies and consulate generals in Germany. Among other they show in detail how a micro-chip was implanted in a Hamburger eaten by Barack Obama at a state dinner with Angela Merkel. (Do they serve Hamburgers on those occasions? Seems like I’m getting carried away here, but never mind, you get the point.) That microchop then recorded a private conversation between Mr. Obama and Wladimir Putin in which Obama referred to the Germans as “Fritzs and Krauts.” No, hang on, I got it wrong again: Angela ate the microchip, accidentally, and she, in a convesration with Putin, referred to the US as a rogue state. Somewhere along that line.

Meanwhile, from Iceland Gerhard Bauden flees to Canada from where he plans to seek asylum in, hmm, Taiwan?, Indonesia? – whatever; because the German authorites have revoked his passport he is eventually stuck in the Montréal airport transit zone.

When notoriously patriotic politicians and Bible Belt inhabitants in the US get a bit worked up about the incidient and demand explanations from Germany, the German authorities respond that they’ve handed over the case to the BND to validate the accusations leveled against the BND; we can skip over the detail concerning further reactions sparked in certain rogue countries such as, see above.

What’s more important is that the German authorities now issue a friendly request to their Canadian ally to extradite Mr. Bauden and send him back to German, obviously so that he can help the BND validate the documents that he stole from the BND.

You work out the rest of that story.

Alive & Kicking: Narratology!

Just returned from the “International Conference on Narrative” which was hosted at Manchester Metropolitan University this year – many thanks to our splendid local hosts, Ginette Carpenter and Paul Wake, for organizing a stimulating and smoothly run conference with a rich programme, excellent and friendly support for delegates in a town that has a fascinating and real vibe: Manchester! – The ISSN (International Society for the Study of Narrative) conferences are not “hard core” narratologist events, but rather bring together researchers from various quarters – those who are interested in particular narrative genres, narrative works of art in different media, non-fictional story telling, cultural studies based approaches, literary and media criticism, and of course also theoretical work. However, this year both day one and two started with a block on “Contemporary Narrative Theory”, and in addition to that a number of papers in the main program then also addressed theoretical issues. All in all this demonstrated how the theoretical work on narrative which is perhaps mainly, but certainly not exclusively of a narratological vein nowadays provides a common ground for many of those who are interested in the phenomenon of narrative representation.Just returned from the “International Conference on Narrative” which was hosted at Manchester Metropolitan University this year – many thanks to our splendid local hosts, Ginette Carpenter and Paul Wake, for organizing a stimulating and smoothly run conference with a rich programme, excellent and friendly support for delegates in a town that has a fascinating and real vibe: Manchester! – The ISSN (International Society for the Study of Narrative) conferences are not “hard core” narratologist events, but rather bring together researchers from various quarters – those who are interested in particular narrative genres, narrative works of art in different media, non-fictional story telling, cultural studies based approaches, literary and media criticism, and of course also theoretical work. However, this year both day one and two started with a block on “Contemporary Narrative Theory”, and in addition to that a number of papers in the main program then also addressed theoretical issues. All in all this demonstrated how the theoretical work on narrative which is perhaps mainly, but certainly not exclusively of a narratological vein nowadays provides a common ground for many of those who are interested in the phenomenon of narrative representation.

I listened to many excellent papers and can unfortunately only highlight a few. Richard Walsh’s ‘Some Commonsensical and Uncontentious Thesis on Narrative and Spatiality; Leavened by a Perverse Reading of Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy‘ was big fun, particularly the perverse part of it. Ruth Page’s ‘Counter Narratives and Controversial Crimes: The Wikipedia Article for the Murder of Meredith Kercher‘ demonstrated a fascinating piece of research into the variation that stories can undergoe during the process of repeated editing in Wikipedia. Ruth combined this with a cross-cultural comparison of the Kercher-articles in the English/US and Italian Wikipedia versions. Obviously, this is the type of work that one would want to support with a tool like CATMA – but in order to do that we will first have to integrate a collation module! It’s now on the road map… Johanne Helbo Bondergaard’s ‘Forensic Literature: Evidence and Fictionality in Contemporary Memory Narratives’ and Inke Gunia’s ‘On Evidence Regarding to Factuality and Fictionality’ were both not entirely new to me (Inke and I are working together in a research project on ‘Factuality’ and Johanna has presented at one of our workshops) but have progressed further significantly.

Johanne is also one of a number of Danish colleagues from Aarhus University with whom we (that is, members of Hamburg’s Interdisciplinary Centre for Narratology) have started a collaboration that will hopefully result in a larger joint research project. Her colleague Louise Brix Jacobson presented an interesting paper on ‘Fictionalization as Performative Self-Fashioning Strategy’, and Simona Zetterberg Gjerlevsen tackled Richard Walsh head on with her lucid contribution ‘Fictionality in Terms of Speech Act Theory’: and the ensuing debate between her and Richard showed that that’s exactly how academic discourse should be conducted – open, unafraid of controversy and friendly! I really enjoyed that – a PhD student taking one of her mentors to task in public; great! And great how Richard responded!

On Friday afternoon there was a special panel that paid tribute to Gerald Prince and his ‘Contribution to Narratology: A celebration’. Three witty and polished papers by Susan S.Lanser, Thomas Pavel and Hilary Dannenberg each threw their own light not only onto Prince’s work, but they also brought together facets of a more personal image of Gerald Prince to whom I, like many others, am deaply indebted. INdeed, for me this was a ‘double feature’ because one of the speakers himself, Thomas Pavel, is the narratologist who had the greatest impact on me personally: his 1986 “Poetics of Plot” is the study that opened my eyes to the possibility of combining narratology with a computational approach. And so it was a great honor and pleasure for me to talk to Thomas after the panel and exchange some thoughts on the fruitful tension between formalism and content oriented literary criticism. Thomas’s “narratological journey”, I think, has marked a path that I have unconsciously followed myself; as he put it: “The older I get the more I become interested in content again. I mean, let us be honest – do we really read Madame Bovary because of its formal features, or do we read it because we’re interested in the fate of that stupid woman?” He’s right, and all one can say to this is quote Barthes who (well, I don’t quite know where, and I am not even absolutely sure it actually WAS Barthes who said this; couldn’t it also have been Jacobson or Levy-Strauss? Never mind) said something along the line of “A little bit of Formalism takes us away from content. A lot of Formalism brings us back to it.”

way from content. A lot of Formalism brings us back to it.”

On the “computationalists” vs. “humanists” debate

The following is my five cents on an issue recently raised (again) on HUMANIST, the electronic online forum for the Digital Humanities. Following Mark Finlayson’s announcement of the “Computational Models of Narrative” workshop at Hamburg University, 3-6 August 2013 (I’m honored to be a co-host) a debate arose as to whether computational sciences and AI on the one side, and the traditional humanities on the other could really be brought into fruitful contact – or whether either side was rather preoccupied with defending its turf. In his HUMANIST posting 27.124 Willard McCarty then raised the question: “Usually when we say “I am of two minds about that” we take the person simply to be undecided. I wonder if we digital humanists might think of ourselves as being perpetually undecided?” – Here’s my reply of 16 June 2013:

————————–

Let me add just two quotes to Willard’s collection. Both are by the same (German) author, and both date some 130 years before C.P. Snow, around 1820/1830. This is the first:

»Ich kann ein Differentiale finden, und einen Vers machen; sind das nicht die beiden Enden der menschlichen Fähigkeit?« („I can identify a differential, and I can make a verse; are these not the two peaks of human competence?“)

Against the backdrop of the new, evolving natural sciences and referring back to Leibniz’ differential calculus as one of the most abstract mathematical break throughs, the German Romantic poet Heinrich von Kleist tries to uphold – or rather, re-vitalize – the Humanist idea of a unified culture of scientific knowledge and Arts, of a dialect of formal mathematical abstraction and subjective “verse” that merges representation and emotion.

Moreover, Kleist already has the idea of declaring this holistic philosophical and epistemological stance as a potential methodology – for him it is not just a personal vision. In another letter, he writes: „One could distinguish two classes of men: those who are capable of metaphors, and those who are capable of formulae. Those who are capable of both are too few; they do not form a class.“

The problems and hick ups that we encounter in our interdisciplinary discourse among “computationalists” and “humanists” were thus reflected upon long before computers as we know them emerged (OK, the idea of a computer did of course already exist – Leibniz again). So let’s face it: technology really only plays a marginal role in this epistemological and methodological exchange and meeting/clashing of minds.

What is more important, I believe, is the conceptual and functional distinction which we need to reflect over and over again. To me this distinction is demarcated by two fault lines.

One, the methodological centre of gravity in the humanities is hermeneutics: trying to understand and interpret phenomena in terms of their relevance and impact on humanity, and analysing and modelling these phenomena as experiences that are historically contingent. And because of that, whatever we do and whatever knowledge (or nonsense) we produce in the Humanities is ‘indexical’ – it points back at the interpreting subject and at the society that grapples with the phenomena at hand. To make matters even more complicated, that (perceived or real ‘knowledge’) influences the interpreting observer in a dynamic fashion. Now of course Heisenberg and Einstein formulated insights about the principle constraints of scientific observation that one can read as similar, at least in a somewhat metaphorical sense. But the natural sciences are not pulled towards a hermeneutic centre (what indeed are they being pulled towards? Logic per se? A Platonian worm hole?) I’m pretty certain that my (highly uninformed) musings about the nature of Higgs’ particles will in my life time not produce any response in nature. Atoms don’t really give a damn about whose observing them and for what purpose – humans and human societies however do. In other words, though the late 19th century programmatic definition of “Geisteswissenschaften” by Dilthey and others and the forcefully declared dichotomy between the natural and the ‘moral’/human sciences may be outdated, but it’s not irrelevant – and so are other attempts (John Stuart Mill, Hegel, etc. etc..) at categorizing two ideal types (because that’s what they really are; neither type has ever manifested itself in any science in its pure form) of methodology.

The second fault line, as I perceive it, separates the terrain in terms of the concepts of discreteness and continuity. The former is the natural domain of the digital and binary logic – segment phenomena, count them, find a useful metric, calculate them, model them numerically, etc. The latter is the prerogative of our human sensual and intellectual apparatus – we can handle the fuzzy, the ambiguous, the contradictory, the speculative and under defined, and the more robust or consciously reflected our mind’s ‘home base’, i.e. our sense of identity as a functional construct is, the better we can perform this task. We can decide to hear the melody, not the individual notes – and we can decide to do the opposite as well. And those who do that often enough realize that it is this power of being able to switch our conceptual outlook at the world that, paradoxically as it may seem, stabilizes the core. Call it sublimation, call it dialectics – if nothing else it’s more fun!

The lamented conflict between “computationalists” and “humanists” arises as soon as we become afraid of our own courage and shy away from jumping across these two fault lines. Let’s cut through that fear. The task remains, as Kleist so aptly put it, to “become capable of both” – the metaphor and the formula, the verse and the calculus, the musical score as well as the melody and the tear. That’s a borderline experience, no doubt, and those who prefer to pitch their tent in the comfortable centre of either laager don’t run the risk of questioning their own philosophical, epistemological and ethical identity as easily as the ‘Stalkers’ (in the Tarkowskian sense). But thankfully, that’s not the intellectual terrain where the evolving DH ‘tribe’ hunts and gathers.

Chris

Dead Languages and Digital Humanities – Gastvortrag von Dr. Lieve Van Hoof (Uni Ghent)

Im Rahmen meiner aktuellen Vorlesung “Einführung in die Digital Humanities” hält Lieve Van Hoof diesen Gastvortrag

Datum: 25.06.2013

Ort: Phil B

Zeit: 16:15 – 17:45

Jeder kennt Facebook, und alle reden heute vom “Netzwerken” – aber kaum jemand weiß, was für ein faszinierendes Netzwerk bereits das kulturelle und soziale Leben der Antike darstellte. In ihrem Gastvortrag stellt Dr. Van Hoof die Anwendung des Digital Humanities-Verfahrens der sog. “Social network analysis (SNA)” in den Altertumswissenschaften vor und demonstriert am Beispiel der Korrespondenz des antiken Gelehrten Libanius (314-393 A.D.), welche Erkenntnisse und neue Forschungsfragen dieses Verfahren generieren kann.

Dr. Lieve Van Hoof war Postdoktorandin an der Universität Leuven, sodann Humboldt-Stipendiatin (Humboldt-Forschungsstipendium für erfahrene Wissenschaftler) an der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn und bis Mai 2013 Mitarbeiterin am Lichtenberg-Kolleg des Göttingen Institute of Advanced Studies. Im Juni 2013 tritt sie eine PostDoc-Stelle im Department of History an der Universität Ghent an.

Digital Museums and Cultural Landscapes in London – Gastvortrag von James Hemsley und Nick Lambert

Im Rahmen meiner aktuellen Vorlesung “Einführung in die Digital Humanities” habe ich drei auswärtige KollegInnen für zwei Gastvorträge gewinnen können. Den Auftakt machen James Hemsley und Nick Lambert:

Datum: 18.06.2013

Ort: Phil B

Zeit: 16:15 – 17:45

Dr. James R. Hemsley und Dr. Nicholas Lambert vom Birkbeck College in London geben in diesem Gastvortrag einen Überblick über die sehr lebendige, facettenreiche digitale Museums- und Kunstszene in London und disktuieren deren Entwicklungsperspektiven im Kontext der aktuellen Digital Humanities-Initiativen.

Dr. James R. Hemsley studierte Mathematik an der University of Oxford und erwarb seinen Ph.D am Imperial College, London. Er ist seit über 25 Jahren im Schnittbereich “Kunst & Kulturerbe / Computing und Telekommunikation” tätig. Er war u.a. 1989-1991 Projektmanager des EU-VASARI Projekts und ist Begründer der EVA Konferenzen (http://www.eva-conferences.com/eva_london), auf denen seit 1990 das Thema “Digitalisierung von Kulturerbe und Museen” diskutiert wird. Seit seiner Emeritierung ist Hemsley tätig als Berater für das Ravensbourne College, London; außerdem als ehrenamtlicher Forscher im VASARI Centre des Birkbeck College.

Dr. Nicholas Lambert ist Lecturer in Digital Art and Culture am Birkbeck College. Er war zuvor u.a. Lecturer am Ravensbourne College of Design und Principal Investigator (Projektleiter) des Forschungsprojekts “Computer Art and Technocultures (CAT)” des Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC, entspricht der DFG). Lambert wurde 2003 im Department of the History of Art, Oxford University bei Prof. Martin Kemp mit der Studie “A Critical Examination of ‘Computer Art’: Its History and Application” zum D.Phil promoviert.

What are the Digital Humanities? – Public PhD Seminar @ Oslo University

Just came back from the public PhD seminar “What are the Digital Humanities?” that took place at Oslo University, Norway June 14-15. This was a very enriching experience on two accounts:

One, of course, the programme (which you can call up at www.whataredigitalhumanities2013.wordpress.com). Among the highlights were a concise introductory keynote by Oyvind Eide that reflected directly on the conference theme and five papers dedicated to some longer running, high-profile DH projects run and/or initiated by established Norwegian researchers (Espen S.Ore, Jill Walker Rettberg, Oddrun Gronvik, Stine Brenna Taugbol and Christian-Emil Smith Ore). This is highly significant work and it demonstrates, once again, how the so-called “small countries” can often provide for a more agile, supportive environment for innovative scientific paradigms.

And then what really fascinated me were three presentations made by young “up-and-coming” DH scholars:

Laetitia Le Chatton (Uni Bergen) talked about “Conversational Machines and Their Role in DH”. What is a “conversational machine”? Well, check out Laetitia’s project facebook page to learn more about her pretty quirky take on chatterbots. The machine that Laetitia and her team have designed is advertised as “The engine that speaks your mind” and is based on a radically new approach that builds on communication theory more than anything. Pity it’s not yet running as a web service – so I will have try and get Laetitia to visit our heureCLÉA team in Hamburg and do a live demo for us.

Scott Weingart (Indiana University) talked on “Weakly Connecting Early Modern Science” and the principles underlying Social Network Analysis (SNA). Scott claimed that he had mixed up his slides and left the correct one in the US – well, if that’s the level he achieves with the wrong slides then the mind boggles as to what he’ll do with the correct ones! This was a very well thought-out and transparent introduction to the topic. Scott’s current focus is on the “Republic of Letters”, i.e. the Early Modern Age science discourse that is documented in the form of thousands of letters exchanged among thinkers throughout Europe. For more check out his blog. Must get him to Hamburg too, hopefully in October!

The third paper by a young scholar was presented by Lieve Van Hoof who is about to take up a position at Ghent University. Lieve works in SNA as well, but her area of expertise is in Classics rather than Early Modernity: she demonstrated how an SNA of some 1500 letters written to and by Libenius of Antioch (314-393 A.D.) can cast new light on some assumptions and hypothesis which traditional Classics has formed about the practice of discourse and the formation of ideas in Antiquity. I’m glad I managed to convince Lieve to come to Hamburg straight away, i.e. in two weeks time, and to present her work in my current lecture “Introduction to DH” on 25 June 2013.

Unfortunately I could not stay long enough to listen to Emma Ewadotter’s presentation on HUMlab as I had to catch my flight back to Hamburg via Copenhagen (why did it take me 1 1/2 hs to get to Oslo, but 7 hs to get back? I sometimes get the impression that I’m spending half my life in airport lounges. That’s risky to humanity because sooner or later I will strangle one of the human appendixes of smartphones who seem to believe that the entire world MUST partake in the fate of Auntie Carol’s basset hound, or the latest war story about the-deal-we-almost-struck-with-the-Chinese-but-now-I’m-on-my-way-to-Chicago-and-don’t-forget-to-call-Rick-about-the-discount-on-the-Scud-missile-shipment).

The second and more general thing that impressed me is how a new generation of young DH scholars is taking up the reigns and beginning to transform our field! This energy and enthusiasm is really, really inspiring! And just think about it: a young PhD student organizes such an event almost single handedly, gets substantial funds, deals with all the admin, flies in people from all over Europe and the US and gets the ball rolling in the discussion on “Digitale Humaniora i Norge”! Well done, Annika and thanks a lot for all your effort! (Annika Rockenberger presented on „Georg Greflinger – Digitale Archiv Edition sämtlicher Werke und Schriften. Pilotprojekt: Ethica Complementoria (1645)“ at last year’s DH Unconference prior to the DH 2012 – a mammoth task for a PhD project!)

“One billion rising” – taking a stand against rape and brutality affecting women and children!”

KNYSNA NEWS – Knysna resident, Angela Meister, is so incensed by the violent rapes that keep escalating in the world that she made up her mind to take a stand.

After reading about the campaign, One Billion Rising which urges each person to “take a simple pledge this Thursday [Febuary 14] to do one thing in the next year to end violence against women”, she decided to call on all her family, friends and their friends to join her in creating awareness of the international One Billion Rising movement as well as the fact that a woman is raped in South Africa every four minutes.

“Over one billion women have been raped in the world and that number is rising as we speak,” said a passionate Meister.

It made no difference whatsoever that only she, her husband Christoph, their domestic worker Nomalanga Kinana and a friend stood proudly at the Knysna Mall from 13:00, handing out brochures and telling all who would listen to join the One Billion Rising movement and to take a stand.

“If we would all just stand together and sign the petition which is an appeal to President Zuma to not only pass stringent laws regarding rape, but to make money available to support programmes which will hopefully ultimately change the psychology of rape, we may have made a small difference in a global epidemic,” she said.

http://www.knysnaplettherald.com/news.aspx?id=45483&h=Taking-a-stand

Ein Blogpost über ein Buch über einen Film über eine Reise zu einem Zimmer

Manchmal lese ich auch Bücher. Zu Weihnachten habe ich mir eines von Geoff Dyer geschenkt, auf das ich durch eine SZ-Rezension aufmerksam geworden bin: “Die Zone. Ein Buch über einen Film über eine Reise zu einem Zimmer” (München 2012; leider war ich zu ungeduldig, mir das englische Original zu besorgen, habe es also in der zwar insgesamt soliden, aber naturgemäß den englischen Sprachwitz und die Lakonie wohl nur bedingt vermittelnden Übersetzung von Marion Kagerer gelesen, mit der ich dennoch zufrieden war – bis ich auf ein Verb stieß, das mir immer noch auf der Zunge liegt wie ein Gemisch aus Heurigem und süßem Senf: “schlägern.” Jawohl, “schlägern” – S.178. Ich dachte erst, ich hab’ was überlesen; ging’s da irgendwo um Tennis oder Squash? Nein. Es geht um drei Männer, die sich prügeln, raufen, schlagen, hauen. Eben Schläger, die sich, wie könnte es also anders sein, “schlägern”. So wie z.B. Autofahrer naturgemäß “fahrern”, Zahnärzte “bohrern” und Rechner “rechnern”. Ich habe nie gedacht, dass Worte einen regelrechten Geschmack annehmen können, aber “schlägern” kanns. Und es schmeckt – sensu literalis ebenso wie sensu schwytzerdütsch, d.h. gustatorisch wie olfaktorisch – nun mal wie eine tote Weißwurst. – Ende des geschmäcklerischen Exkurses. Ja Himmel, habt’s Ihr keine Lektoren bei Schirmer-Mosel?)

Die “Zone”, die dieses Buch im Titel trägt, ist eine mystische, verbotene Region in Andrej Tarkovskijs Kultfilm “Stalker” aus dem Jahr 1979 (“beinharter Art House-Stuff”, wie es auf weltbild.de im Artikel zum Buch treffend heißt). Stalker, die Hauptfigur, führt in dem Film zwei Männer in dieses Gebiet, um sie zu einem Zimmer in dessen Mitte zu bringen, das im Rufe steht, die geheimsten Wünsche desjenigen, der es betritt, zu erfüllen. Den Inhalt des Films ausführlicher darzulegen und zu kommentieren hieße, das Buch Dyers gleich noch einmal zu schreiben. Exakt 200 Druckseiten lang verknüpft Dyers Text eine minutiöse Schilderung der Handlung und kinematographischen Umsetzung (ursprünglich sollte diese Inhaltsangabe 1:1 den 144 Cuts des Films folgen, aber irgendwann schmiss Dyer, wie er anmerkt, dieses denn doch recht mechanische Konzept zum Glück über Bord) mit gerne etwas schnoddrigen interpretierenden Anmerkungen, dafür aber umso gehaltvolleren Assoziationen und interessanten Exkursen in den hier und da ausufernden Fußnoten. Ich glaube nicht, dass irgendjemand, der den Film nicht kennt (und von ihm so fasziniert und angesprochen ist, wie Dyer es ist und wie ich selbst es immer noch bin), mit diesem eigenartigen, mehrspurigen Close Reading viel anfangen kann. Aber wer diese Voraussetzungen mitbringt, darf sich auf etwas freuen und gefasst machen – nämlich auf die Begegnung mit einer subjektiven Lesart dieses enigmatischen Filmkunstwerks, die dessen Anschlussfähigkeit und Ausdeutbarkeit auf eine ebenso intelligente wie transparente und ehrliche, persönliche Weise nutzt. Das ist ein wenig so, wie Roland Barthes’ “S/Z” zu lesen, wenn auch nicht mit einem derartigen programmatischen Anspruch.

Jemand anders beim Sehen oder Lesen zuzuschauen ist ja eigentlich nur dann gerechtfertigt, wenn man Voyeur, Psychoanalytiker oder mangels Mut zum hermeneutischen Risiko auf Ersatzerfahrungen sich kaprizierender Literaturwissenschaftler ist. Sicher, Dyers Lesart des Films ist ‘adaptiv’, d.h. seine Motivation ist eine sehr persönliche, man könnte vielleicht sagen: es geht um einen Problemlösungsversuch. Aber das Problem, um das es Dyer mit, ebenso wie Tarkovskij in “Stalker” geht, ist eines, das uns alle betrifft – es ist das Rätsel des Wunsches, oder genauer, des Wünschens. Was ist das für ein eigentümliches Vermögen, das uns so viel Kraft gibt und Energie, solange es sich auf ein Abwesendes, noch nicht Gewordenes richtet? Diese Frage lässt sich ja nicht mit dem Hinweis auf die triviale Erfahrung klären, dass der Wunsch selbst im Augenblick seiner Erfüllung kollabiert. Wünschen-Können mag zwar, in der Dimension des Objektbezugs, ex negativo definiert sein als Bezugnahme auf ein notwendig Nicht-Vorhandenes – aber es ist in der Dimension subjektiver Selbsterfahrung zugleich ein positiver Ausdruck des Vermögens zur Transzendenz des je Vorhandenen. In Tarkovskijs “Stalker” geht am Ende keiner der drei Männer (Stalker, Professor, Schriftsteller – alle drei tragen generische Bezeichnungen, keine Eigennamen) in das wunscherfüllende “Zimmer”. Genauso verweigert sich Dyers akribische Rekonstruktion des Inhalts, auch wenn sie mit vielen persönlichen Assoziationen und kulturgeschichtlichen Querverweisen angereichert wird, selber dem Schritt ins “Zimmer” einer symbolischen Gesamtdeutung – was zum größten Teil der Tatsache geschuldet ist, dass seine Anmerkungen zur Bild- und Montageästhetik des Films konsequent deskriptiv bleiben. Und auch das Buchprojekt als solches, das sein Verfasser in zwei oder drei eingestreuten Metakommentaren wiederum als eine Art Reise begreift und reflektiert, tut am Ende genau das, was der Film tut: es entlässt seinen Verfasser und uns wieder in ein Schwarzweiß – aber in ein geläutertes, sepiafarbenes, über das Dyer schreibt:

“Schon das Schwarzweiß von Stalker als schwarzweiß zu bezeichnen heißt, das Gesehene mit einem unangebrachten Verweis auf den Regenbogen zu färben. Technisch erzielte man den konzentrierten Sepiaton, indem man in Farbe drehte und schwarzweiß entwickelte. Das Ergebnis ist eine Art Submonochromie mit so komprimiertem Spektrum, dass eine Energiequelle daraus entstehen könnte, wie Öl und fast so dunkel, aber dazu mit einem goldenen Schimmer.”

Tarkovskijs Stalker ist, wie Dyer behauptet, nicht einfach nur ein “großartiger Film”, sondern “seinetwegen wurde das Kino erfunden.” Ich fand das Statement (klar, das fetzt und steht deshalb auch auf dem Rücken des Covers und im Untertitel zu dem Bild auf meiner ‘Projekte’-Seite hier) zunächst catchy, dann aber doch etwas nichtssagend. Aber nachdem ich den Film wieder gesehen habe, denke ich, es ist was dran – wenngleich diese Tarkovskijsche Ästhetik des negativen Sinns, der Anti-Symbolik, der radikalen ikonographischen Vordergründigkeit doch auch ein wenig manieristisch und existentialistisch daherkommt. Aber so waren wir eben drauf, damals, in den späten 1970ern, als alles anfing, post- zu werden, und man sich Stalker drei Mal hintereinander im Abaton anschaute. Nur: um so eine All-Behauptung jenseits des temporären Aufmerksamkeitseffekts sinnvoll zu machen, müsste Dyer dann doch das tun, was er so sorgsam vermeidet, nämlich seinem enthusiastischen ästhetischen Urteil ein philosophisches Fundament einziehen. Es gibt Ansätze dazu, die sich mit Tarkovskijs sehr eigener Begabung auseinandersetzen, uns zu einer filmischen Variante jener Sehweise einzuladen, die Uwe Timm im literarischen Feld als eine “Ästhetik des Alltags” und der Dinge bezeichnet – nämlich da, wo Tarkovskij seine Kamera geduldig Objekte betrachten lässt, die ihrem pragmatischen Zweck abhanden gekommen sind (zerbrochene Kacheln; eine Spritze im Wasser; verrostete Eisenstücke) und daraus einen poetischen Freiraum zu schöpfen scheinen, der aber garnicht ihr eigenes Verdienst ist, sondern das des Betrachters, der sich auf sie einlässt. Tarkovskij selbst jedenfalls hat solche philosophierenden Selbstkommentare keinesfalls gescheut. O-Ton Tarkovskij: “The allotted function of art is not, as is often assumed, to put across ideas, to propagate thoughts, to serve as example. The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.” – A propos, eine Anspielung, die Dyer nicht gesehen hat: der Motorradfahrer in der Szene, als die drei Männer mit dem Landrover (KEIN Jeep!!!) über das verlassene Industriegelände in die Randzone der Zone rumpeln, stammt aus Jean Cocteaus Orphée von 1949 – das muss man doch raffen!

“Standing at the Sky’s Edge” von Richard Hawley – (m)eine “CD of the year”

Vielleicht doch ein bißchen hoch gehängt. Aber eine wirkliche Entdeckung war für mich Richard Hawley dennoch, auf den ich durch eine Konzertrezension im Oktober 2012 gestoßen bin – denn wenn man über einen ‘Crooner’, also einen Schnulzensänger, sowas wie dies hier liest, dann muss ich einfach zugreifen:

“Sicher vor dem ewigen Regen Yorkshires hat Richard Hawley in den Sheffielder Yellow Arch Studios ein Album aufgenommen, das – anders als das Leben, von dem es handelt – in jeder Sekunde hält, was es verspricht: dass einmal, und sei es in der Kunst, alles aus einem Guss sein möge. “Truelove”s Gutter” ist ein unaffektiertes, unzeitgemäßes und deshalb vollkommen zeitloses Album. Man steigt aus dieser CD, die eine einzige große Geschichte erzählt von einem Mann, seiner Frau, seinen Freunden und der trostspendenden Kraft der Kunst, nicht einfach aus. Und man wird diese großen Songs auch gar nicht mehr los.”

Das ist jetzt nicht aus der Rezension und bezieht sich auch nicht auf Standing at the Sky’s Edge, sondern stammt aus dem SZ-Artikel von Alexander Gorkow aus Anlass des Erscheinens der CD Truelove’s Gutter vom 20.09.2009. Tatsächlich hört sich Hawley auf Truelove’s Gutter schon im ersten Song an wie eine Art doppelt weichgespülter Roy Orbison. Dass es dann aber dennoch nicht schnulzig wird, verdankt sich den intelligenten Texten (O-Ton Gorkow: “Richard Hawley ist Brite, also deprimiert im besten Sinne.” Das trifft’s genau…) und der subtilen Orchestrierung, die mit Überraschungen aufzuwarten hat, die von Ligeti-Hintergrund-Einsprengseln à la “2001 Odyssee im Weltraum” bis zum plötzlichen Aufdrehen zu einer Phil Spector-mäßigen “Wall of Sound” reichen, die einen einfach wegbläst (und die mithörenden Nachbarn auch; tough luck; dient ja einer guten Sache. Eben KUNST.)

Nun gut, das höre ich mir also ein paar Mal an im Verlaufe einiger Wochen; passt zur immer trüber werdenden Jahreszeit – intelligente Melancholie gepaart mit unergründlich grundlosem Durchhaltewillen, nein, nicht grundlos, denn da bleibt trotz allem noch “true love”. Worauf der Titel der CD aber nur sekundär Bezug nimmt; tatsächlich verdankt er sich einem Straßennamen in Sheffield, der wiederum auf einen Mr.Truelove rekuriert, der als Wirt von den Anwohnern, die ihren Dreck in die Gosse, den “gutter” schütteten, einen Zoll erhoben haben soll. Der Titel ist also so eine Art private joke, britisch – s.o..

Nach dem vielleicht fünften Mal Anhören steigt dann aber doch allmählich eine Frage in mir auf: ist das jetzt Hawleys ‘Fach’, dieser intelligent gebrochene, postmodern gewendete Roy Orbison-Widergänger? Oder ist da noch mehr? Der Mann war ja immerhin mal Gitarrist bei “PULP”. Ich lese ein bißchen über ihn nach – und lade mir dann das neue Album “Standing at the Sky’s Edge” herunter, Programm laut Hawley: “„Ich wollte unbedingt weg von dieser Orchestrierung der bisherigen Alben und einfach eine Live-Scheibe einspielen mit zwei Gitarren, Bass, Schlagzeug und Raketengetöse!“ Und das gibt’s nun wirklich vom Feinsten, sublimes Raketengetöse, wie ich eigentlich schon am 29.4.2012 im Curt-Magazin hätte vor-lesen können:

Schon der erste Titel „She brings the sunlight“ macht klar: Es gibt nur einen, der den ehemaligen PULP-Gitarristen toppen kann – er selbst. Es beginnt psychedelisch mit sanft-schmeichelnden Sitars, dann bauen sich Gitarrenwände aus roughen Soli auf, und über allem schwebt der intensive, Skrotum zusammenziehende Bariton von Hawley – Musik für Männer des 21. Jahrhunderts.”

Auch in Standing at the Sky’s Edge findet Hawley nach 3, 4 Stücken gelegentlich wieder zum Orbison-Sound zurück; kein Wunder bei der Stimme. Aber es ist dieser erstaunliche Kontrast, der das Ganze zum Genuss macht. Kaufen, Hören. Warum nicht gleich jetzt – es ist das beste Randgruppenerlebnis, dass man sich wünschen kann!

Vielleicht doch ein bißchen hoch gehängt. Aber eine wirkliche Entdeckung war für mich Richard Hawley dennoch, auf den ich durch eine Konzertrezension im Oktober 2012 gestoßen bin – denn wenn man über einen ‘Crooner’, also einen Schnulzensänger, sowas wie dies hier liest, dann muss ich einfach zugreifen:

“Sicher vor dem ewigen Regen Yorkshires hat Richard Hawley in den Sheffielder Yellow Arch Studios ein Album aufgenommen, das – anders als das Leben, von dem es handelt – in jeder Sekunde hält, was es verspricht: dass einmal, und sei es in der Kunst, alles aus einem Guss sein möge. “Truelove”s Gutter” ist ein unaffektiertes, unzeitgemäßes und deshalb vollkommen zeitloses Album. Man steigt aus dieser CD, die eine einzige große Geschichte erzählt von einem Mann, seiner Frau, seinen Freunden und der trostspendenden Kraft der Kunst, nicht einfach aus. Und man wird diese großen Songs auch gar nicht mehr los.”

Das ist jetzt nicht aus der Rezension und bezieht sich auch nicht auf Standing at the Sky’s Edge, sondern stammt aus dem SZ-Artikel von Alexander Gorkow aus Anlass des Erscheinens der CD Truelove’s Gutter vom 20.09.2009. Tatsächlich hört sich Hawley auf Truelove’s Gutter schon im ersten Song an wie eine Art doppelt weichgespülter Roy Orbison. Dass es dann aber dennoch nicht schnulzig wird, verdankt sich den intelligenten Texten (O-Ton Gorkow: “Richard Hawley ist Brite, also deprimiert im besten Sinne.” Das trifft’s genau…) und der subtilen Orchestrierung, die mit Überraschungen aufzuwarten hat, die von Ligeti-Hintergrund-Einsprengseln à la “2001 Odyssee im Weltraum” bis zum plötzlichen Aufdrehen zu einer Phil Spector-mäßigen “Wall of Sound” reichen, die einen einfach wegbläst (und die mithörenden Nachbarn auch; tough luck; dient ja einer guten Sache. Eben KUNST.)

Nun gut, das höre ich mir also ein paar Mal an im Verlaufe einiger Wochen; passt zur immer trüber werdenden Jahreszeit – intelligente Melancholie gepaart mit unergründlich grundlosem Durchhaltewillen, nein, nicht grundlos, denn da bleibt trotz allem noch “true love”. Worauf der Titel der CD aber nur sekundär Bezug nimmt; tatsächlich verdankt er sich einem Straßennamen in Sheffield, der wiederum auf einen Mr.Truelove rekuriert, der als Wirt von den Anwohnern, die ihren Dreck in die Gosse, den “gutter” schütteten, einen Zoll erhoben haben soll. Der Titel ist also so eine Art private joke, britisch – s.o..

Nach dem vielleicht fünften Mal Anhören steigt dann aber doch allmählich eine Frage in mir auf: ist das jetzt Hawleys ‘Fach’, dieser intelligent gebrochene, postmodern gewendete Roy Orbison-Widergänger? Oder ist da noch mehr? Der Mann war ja immerhin mal Gitarrist bei “PULP”. Ich lese ein bißchen über ihn nach – und lade mir dann das neue Album “Standing at the Sky’s Edge” herunter, Programm laut Hawley: “„Ich wollte unbedingt weg von dieser Orchestrierung der bisherigen Alben und einfach eine Live-Scheibe einspielen mit zwei Gitarren, Bass, Schlagzeug und Raketengetöse!“ Und das gibt’s nun wirklich vom Feinsten, sublimes Raketengetöse, wie ich eigentlich schon am 29.4.2012 im Curt-Magazin hätte vor-lesen können:

Schon der erste Titel „She brings the sunlight“ macht klar: Es gibt nur einen, der den ehemaligen PULP-Gitarristen toppen kann – er selbst. Es beginnt psychedelisch mit sanft-schmeichelnden Sitars, dann bauen sich Gitarrenwände aus roughen Soli auf, und über allem schwebt der intensive, Skrotum zusammenziehende Bariton von Hawley – Musik für Männer des 21. Jahrhunderts.”

Auch in Standing at the Sky’s Edge findet Hawley nach 3, 4 Stücken gelegentlich wieder zum Orbison-Sound zurück; kein Wunder bei der Stimme. Aber es ist dieser erstaunliche Kontrast, der das Ganze zum Genuss macht. Kaufen, Hören. Warum nicht gleich jetzt – es ist das beste Randgruppenerlebnis, dass man sich wünschen kann!